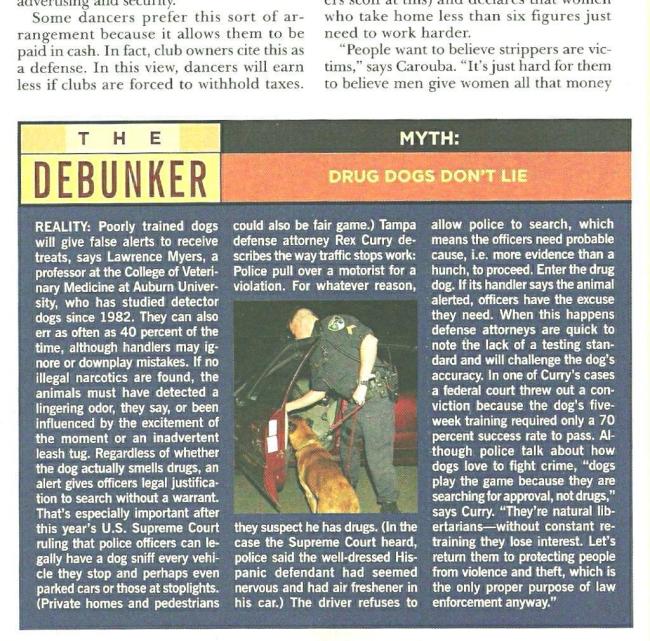

Ellis Curry, Attorney, challenges accuracy of drug dogs

An appeals court throws out a Hillsborough case, saying no evidence was presented to show a drug-sniffing dog's "track record."

By CHRISTOPHER GOFFARD, Times Staff Writer

© St. Petersburg Times

published August 7, 2003

© St. Petersburg Times

published August 7, 2003

TAMPA - Hillsborough sheriff's deputies deployed their drug-detecting dog, Razor, to sniff around the car when they stopped motorist Gary Alan Matheson for a traffic infraction on Hillsborough Avenue.

The German shepherd signaled the presence of drugs, which deputies used as probable cause for the May 1999 search. The search revealed morphine and methamphetamine.

After failing to get the evidence suppressed in court, Matheson pleaded no constest to drug-possession charges. He received probation in 2000.

This week, however, the 2nd District Court of Appeal threw out the case against Matheson, saying the state had not presented any evidence of the dog's "track record" of sniffing out drugs.

The Sheriff's Office acknowledged that it did not keep records of Razor's success rate in the field and that the dog had no training to distinguish between actual drugs and "dead scents" from drugs no longer present.

In its unanimous ruling, the appeals court also noted that Razor had received only five weeks of drug-sniffing training, whereas the Customs Service puts its dogs through a 12-week course and teaches them to disregard residual scents.

The Customs Service requires its dogs to have a perfect record; only half of the dogs complete the program. But the certification program Razor attended requires only 70 percent success.

The court's ruling, which also affects law enforcement in PinellasCounty, does not forbid drug searches by dogs or declare them uniformly unreliable. But without better training, the court ruled, Razor should not have automatically been considered reliable enough to give deputies probable cause for the car search.

"However much we dog lovers may tend to anthropomorphize their behavior, the fact is that dogs are not motivated to acquire skills that will assist them in their chosen profession of detecting contraband," wrote Judge Stevan Northcutt.

Local law agencies say it's too early to speculate on the ruling's impact.

Susan Shanahan, the assistant attorney general who is handling the appeal for the state, said the state probably will ask the 2nd District Court of Appeal for a rehearing.

"The opinion's not final, and policies won't necessarily change until that opinion is final," she said.

The case would potentially have far-reaching implications and could influence cases nationwide, Shanahan said.

Some people are already celebrating the ruling.

"It'll change the way they do their training and record-keeping," said Tampa lawyer Rex Curry, Matheson's defense attorney. He argued Matheson's motion to suppress the drug evidence.

Curry said defense lawyers from across the country already are asking him for copies of his suppression motion for use in their own cases involving drug-sniffing dogs.

"The whole defense community's really barking about this," he said.

Hillsborough Sheriff's Office spokesman Lt. Rod Reder said the office will examine the ruling.

"We hope this really can be overturned," Reder said. "We find the dogs to be a very powerful and fair tool in the war on drugs."

In the past year, the 10 dogs the Sheriff's Office uses for drug searches and routine patrol handled 1,595 calls. Of those, 378 were drug searches of houses and cars, Reder said.

St. Petersburg police officials didn't want to comment on the decision, saying they needed time to research its implications.

Deputies in charge of the Pinellas County Sheriff's Office canine unit have been developing a system to track their dogs' success rates, said Detective Tim Goodman, an agency spokesman.

A supplement noting whether the dog was successful during a search goes into each report, Goodman said. Deputies have been working on making a master list to track the performance of the dogs. Goodman said the agency also tracks how the dogs perform in training exercises.

- Times staff writers Chris Tisch and Leanora Minai contributed to this report. Christopher Goffard can be reached at 813-226-3337 or goffard@sptimes.com

© Copyright 2003 St. Petersburg Times. All rights reserved

……………………………………

Sniff search

If drug-sniffing dogs can provide probable cause for police to search private vehicles, they should be properly trained and their skills documented.

A Times Editorial

© St. Petersburg Times

published August 19, 2003

© St. Petersburg Times

published August 19, 2003

In an important ruling earlier this month, Florida's 2nd District Court of Appeals said that police dogs used to sniff out illicit narcotics must be properly trained and evaluated, with thorough records kept, before their responses may be deemed reliable. According to the court, the Sheriff's Office in HillsboroughCounty was not doing enough to ensure that its drug-detecting dogs were conditioned to "alert" to contraband alone, as opposed to some other trigger. The ruling laid down a set of guidelines the department will have to follow if it wants to use evidence obtained through the use of the dogs.

The unanimous ruling by a three-judge panel would seem to be just a matter of common sense, but it is sure to be appealed. The Sheriff's Office, like nearly all other law enforcement agencies, uses drug-detecting dogs as a way to circumvent the Constitution's warrant requirement, and it apparently doesn't want this convenient tool scrutinized too closely. But this is precisely the role the courts should play. Rather than being appealed, the court's ruling should be a model for the rest of the state.

In the field, drug-sniffing dogs are often used when a driver, pulled over for a traffic infraction, refuses to give police consent for his vehicle to be searched. The deputy or officer handling the dog will direct it around the perimeter of the car. If the dog alerts to the presence of narcotics, police are deemed to have probable cause and may conduct a legal search of the car's interior.

Why should a driver pulled over for speeding be subject to this intrusive process? If police have no cause to believe the driver is a drug runner, why should dogs be used at all? In truth, they shouldn't be, but the U.S. Supreme Court has said the use of drug-sniffing dogs doesn't constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment, and that means police may deploy them with relative impunity.

There is still a role for the courts, however, in ensuring that dogs are the precision tools for finding drugs that law enforcement claims.

In the current case, a Hillsborough County Sheriff's drug-detecting dog, Razor, was used in May 1999 to smell a car driven by Gary Alan Matheson. He had been stopped for a traffic infraction. After the dog alerted to the presence of drugs, the car was searched and illegal drugs were found. The trial court refused to suppress the evidence, and Matheson, who then pleaded no contest, was given probation.

In reversing the conviction, the state appeals court found that Razor's alert was not reliable, due to the poor training and record-keeping done by the Sheriff's Office. Among many deficiencies, Razor's success and failure rate was not documented, the dog had not been subject to controlled negative testing (where he searches and there are no drugs present), and he had not been given training to ignore residual smells of drugs. While the Customs Service puts its drug-detecting dogs through a 12-week course, Razor's training lasted only five weeks. The court found that this lack of rigor meant his alert on Matheson's car was not reliable and could not justify a search.

Drug-sniffing dogs give police the power to invade our private vehicles - bypassing the need to persuade a judge to issue a warrant. This exception to the Constitution is based entirely on the dependability of the dog's skills. All the court did was to require those skills to be real and documented. That should not be too much to ask.

Matheson v. State, 870 So. 2d 8 - Fla: Dist. Court of Appeals, 2nd Dist. 2003